On the most basic level, starting a collection in photography requires thought about the type of photography you actually like. Possible categories could include black and white, color, landscapes, nudes, living, vintage, documentary etc. Movements in photography are also good ways to define what you are looking for (Modernism, Pictorialism, War Photography etc). This seems simple but knowing how to define what you like is the first step to making successful purchasing decisions. Each of these different categories or movements will have specific knowledge associated with each.

Deepening your knowledge in these areas will help one develop an “eye.” Having an eye for art can come naturally for some but usually it requires years to perfect and is often difficult to obtain and maintain, even for appraisers. For this reason seeing accurate documentation on anything you purchase, and keeping accurate documentation yourself – how you obtained it and when, should be a priority. Building a written inventory will ultimately save you a lot of headaches later on should you want to sell, or the work is stolen or damaged.

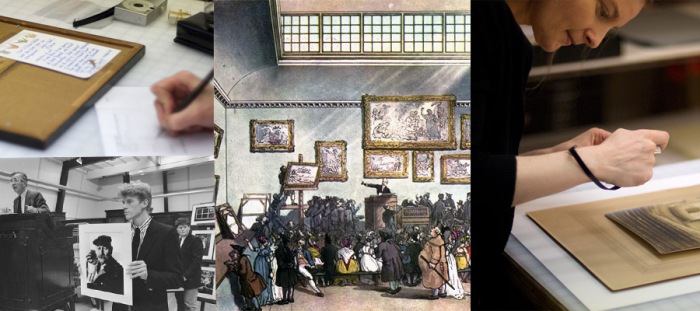

As art experts for the Public Administrator of New York, who handles estates without a will, we experienced just such an issue. Two senior appraisers from OTE were going through piles of mixed objects removed from the apartments, which included jumbles of furniture, framed artworks, collectibles, libraries and miscellaneous materials. Spread across several work tables, was a huge mass of what appeared to be old Kodak film boxes.

Looking through the meticulously maintained photographs, an anomaly considering the rest of the disheveled apartment, they had inadvertently stumbled upon the work of a real artist. Without OTE the collection of photographs by Harry Shunk and Janos Kender, great documentarians of the Paris/New York art scene in the second half of the 20th century, might never have been discovered. The director of a major French museum and those of American museums and film societies arrived to review and the Public Administrator was persuaded to set up an auction for the photographs to be sold as one gigantic lot rather than dispersing them overtime.

Excitingly The Lichtenstein Foundation, thanks to Dorothy Lichtenstein and Jack Cowart, acquired the massive collection at auction for $2 million. After this the foundation began the collating the collection and set up a system to allocate segments of the collection to many museums worldwide. The photographs are now considered invaluable in recording the history of major artists of the second half of the 20th century. A triumphant conclusion to what had almost become a treasure lost forever.

See this post on our website